http://www.karenohanyan.com/eng/#/home

Historical materialism wishes to retain that image of

the past which unexpectedly appears to man

singled out by history at a moment of

danger. The danger affects both the content

of the tradition and its receivers. The same

threat hangs over both: that of becoming

a tool of the ruling classes. In every era

the attempt must be made anew to wrest

tradition away from conformism that is

about to overpower it.

Walter Benjamin

“Theses on the Philosophy of History”5

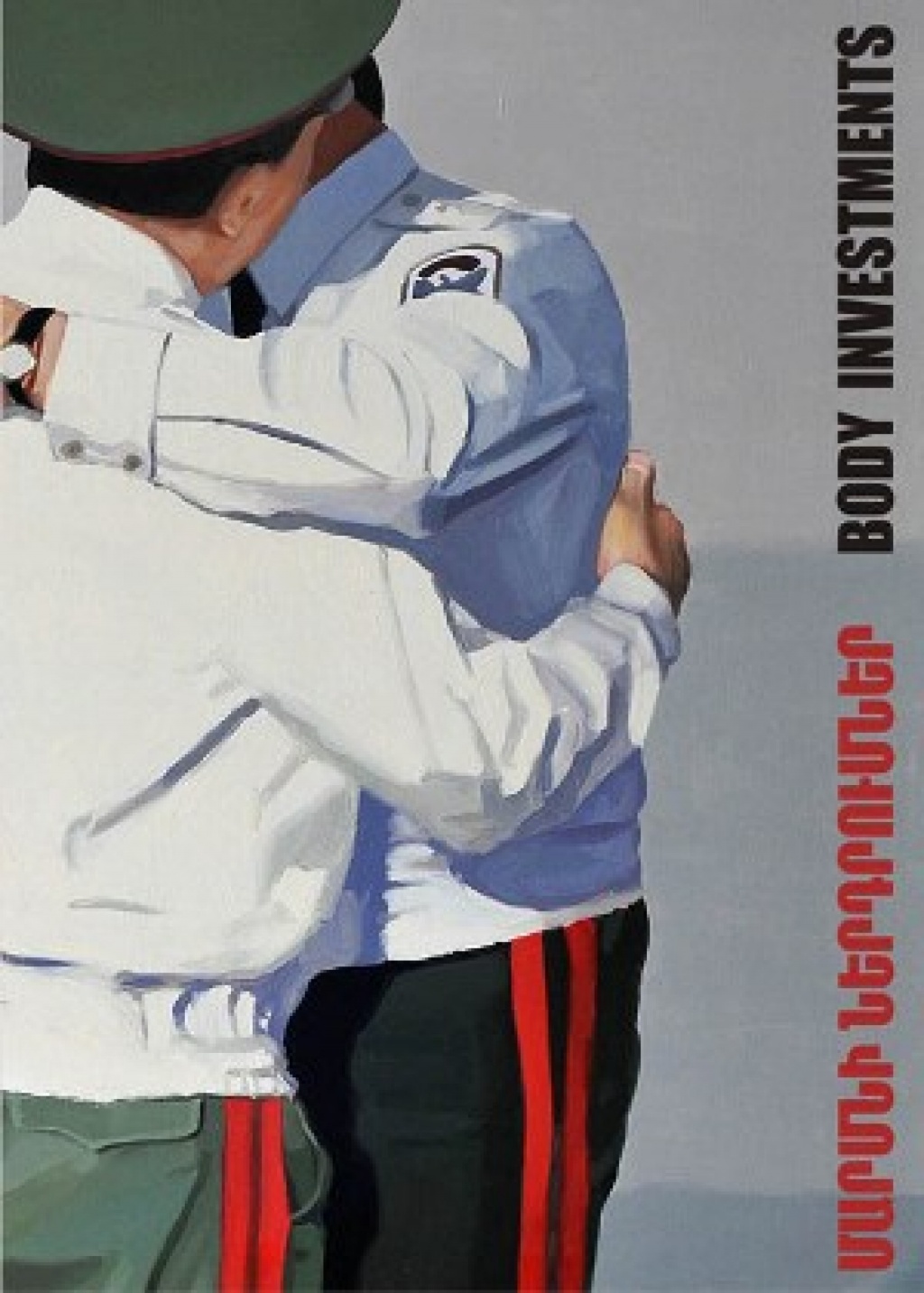

Karen Ohanyan’s “Real Utopias” series, created a few years ago, was ranked among the best paintings of the year 6. I think Ohanyan’s latest series of paintings, “Body Investments,” also deserves such high praise. It is not difficult to find commonalities between these two projects, even if the first is more existential and the second, more political. In “Real Utopias,” the body is viewed both as the last “real thing” and as a utopia – the last free creative space. In “Body Investments,” the body is viewed differently; it is an actual space, a battlefield of micropowers.

In both cases, the insurmountable drive to discover the real can be seen. As a painter, Karen Ohanyan’s standpoint is really quite strong, limited only by his own perception, conscience and sincerity. Ohanyan strives to overcome the confusion, fear and depression that have infected our society. In one of his interviews, Ohanyan said, “To understand my art, you have to be oppressed, but you have to realize that you are oppressed and that consequently, you need freedom. My art isn’t for our society, because our society doesn’t want freedom, but I don’t blame society, because it is dominated by fear.”

The real Ohanyan strives for, can no longer be based solely on the naive perception of one’s own eye: the view is supplemented by technological possibilities, by the act of necessary inspection. In Michelangelo Antonioni’s film “Blowup,” a photographer, while inspecting his photographs, discovers a body behind the bushes in one of the photos. This is symbolic for contemporary art, which excels classical art through its ability to inspect/explore. Striving for the real, Ohanyan uses a camera. Taking pictures, selecting the best and then, with a projector, transferring those onto large canvases, Ohanyan creates images which can be called “hyperrealistic.”

But what is the role of the photograph? It allows for inspection, to view the image from different perspectives, as if from many angles. Hence the huge canvases and figures in unnaturally large scales: those paintings cannot be embraced through a single perspective, and the eye is forced to take different positions. Through this device Ohanyan’s figures acquire massiveness that stresses their corporeality. The non-verbal comes to the fore, especially the kinesics, the language of gestures, whereas the verbal, the linguistic, becomes secondary. The issue is that during communication we “see” the speech, its content and form, expressiveness and meaning, while hand and eye movements are usually ignored. Gestures can either echo or complete verbal language, but it can also contradict the latter.

Gestures, first of all, tell us about a person’s ability to use his or her own body; they are the expression of body technique. But why is corporeality, the body technique, important? If, from a traditional aesthetic perspective, the body can be called beautiful or disproportionate, corporeality is a social phenomenon. Michel Foucault in his interview “Power and Body” of 1975 says that if it has been possible to produce knowledge on the body, than only through the combination of military and educational disciplines. It was on the basis of power over the body that a physiological and organizational knowledge became possible. Foucault’s archeology of humanities should be built on the exploration of the mechanisms of power invested into the body, gestures and norms of behavior7. It is its affiliation with Foucauldian archeological exploration that the name of the series is based on: “Body Investments.”

Three of the paintings show police officers supervising a football field, a street or demonstrators. In another painting, police officers are embracing one another. But the fifth piece presents a face of a demonstrator who has been assaulted.

Possession begins from possessing one’s own body and the authorities particularly strive to work for the bodies of children and youth, soldiers and police officers – that is, for those bodies that are quite healthy. Ohanyan, by painting police officers who are controlling public spaces or opposition rallies and by showing us their gestures and behavior, uncovers the micropower’s configuration in present-day Armenia. After March 1, 2008, when police forces carried out a bloody massacre of peaceful demonstrators, the power became a power of violence, and basically it was almost completely given up to the police. Both for governing authorities and the opposition this was a time when they became mutually dangerous. In this sense, not only is Ohanyan’s artwork, in Foucault’s sense, “archaeological,” but it is also “historical materialist,” as understood by Benjamin.

In the last three years, the political scene in Armenia has been transformed: new political subjects have appeared, political activism is growing, and the internet has become an important domain of political activities. All of these are possibilities to make audible the voices of social groups which were invisible until then, deafened by the clamor of political leaders. Another characteristic of this state of affairs is that it becomes an extremely important political issue to move freely in public spaces, especially to have the freedom to carry out artistic or political actions. Accordingly, the police officer, who until lately perhaps was basically a guardian of public order, catching criminals, curbing hooligans, or supervising traffic laws, has now become a guardian of political order. His body not only acquired a kind of invulnerable quality (even though theoretically each human body is invulnerable), but also phantasmal qualities of sacredness and delicacy. This is evidenced by the numerous cases against the demonstrators who resisted the police. Particularly important during those cases are the statements made about the delicacy of the police officer’s body. The fantasies woven around the police officer’s body on both sides of the barricades inevitably turn it into an art object; it becomes a sort of “ready-made” like Duchamp’s “Fountain.” Indeed, during the last few years, many canvases and video works exploring the police officer and his body have been produced.

The origin of some police officers’ gestures are easy to find: they are taken from Hollywood films. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that Armenia’s governing authorities have politicized mass culture, forcing show business to become its political ally. The origin of the other group of gestures can also be easily recognized by the Armenian viewers: it is the semi-criminal gestures of the “good guys.” The Armenian government commissions soap operas where the main heroes are “good guys,” criminals and “authorities” of criminal world. And since cinema is mainly the art of behaviors and gestures, this can be viewed as the legitimatization of criminal corporeality. In this way, it is possible to come to the formula of micropower’s configuration in Armenia; it is a mixture of the consumer and the criminal, or, in Foucault’s terms, we have a hybrid of the systems of punishment and discipline. That is how it differs from the purely disciplinary-supervisory configuration of micropower in Western societies.

It also seems that in Ohanyan’s “Body Investments,” the body of a police officer is contrasted with the demonstrator’s corporeality. The former is an organized body, where the organs have certain functions; in border situations the body becomes an attachment to truncheon, a not-ones-own-body. On the contrary, “my body” is the body which is in physical contact with itself. The face of the demonstrator is beaten, pain is the most intensive expression of physical contact with oneself, in this sense it is ones-own-body. “Body Investments” shows the collapse of the ruler’s gesture, the end of bondage and the struggle for defeat, since the winner becomes the power that limits freedom.

Often images taken by hidden cameras were presented as a way of laying blame on March 1 demonstrators. Though the situation was different when images were presented which testified to police officers’ illegal actions. Perhaps, with Ohanyan’s works it is not possible to prosecute a criminal case, but they are revealing evidences too. In this case by looking at the police characters produced by Ohanyan, the viewer steals a part of their power by the very act of his or her viewing.

As it is known, art does not have its own essence, and creative impulses come from other spheres outside of art. Mainly the impulse comes from the political and art is always political, even if this is not recognized. Art’s political context is anchored on the fact that it gets its impulse from body experiences of violence, work and alienation. Armenia’s governing authorities strive to aеstheticize the domination of violence by recruiting show business or soap operas, actors or artists to their campaigns. Karen Ohanyan resists those tendencies by politicizing art.

Vardan Jaloyan

Karen Ohanyan

2009 “Body Investments” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2009 “UND PLATFORM”, Polly-Gallery, Karlsruhe, Germany

2008 “Resistance”, Mkhitar Sebastaci Educational Complex Yerevan, Armenia

2008 “Portrait between modernism and innovation”, ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2007 “Armenian international style ”Akanat-gallery”, Yerevan, Armenia

2007 “Affirmative images” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2007 “Yerevan Crisis” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2007 “No Standart” Museum After Egishe Charents, Yerevan, Armenia

2006 “Real Utopias” Solo Exhibition ACCEA, Yerevan,Armenia

2005 “Liberte-Egalite-Fraternite” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2005 “Photo+” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2005 “Society-Body-Art” Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA), Yerevan, Armenia

2004 “Dream in Dialogue” Armenian Center for Contemporary Experimental Art (ACCEA), Yerevan, Armenia

2003 “OOPS!!” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2003 “Antifreeze” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2002 “Affirmative Art” ACCEA, Yerevan, Armenia

2001 “Exhibition Dedicated to Toumanian” Toumania Museum, Yerevan,Armenia

1999 “Embryo”, AOKS, Yerevan, Armenia

1998 Young Painters Exhibitions, Hamburg, Rostok, Christo, Germany

1993 All-Armenian exhibition “Gifted Children” organized by UN, Yerevan, Armenia

1992 National Children Museum

* since 2007 founding-member of the “ART-Laboratory” NGO

———————————————————————-

5 Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Schoken Books, 1968), p. 255.

6 Vardan Azatyan, “Real Utopias,” Karen Ohanyan: Real Utopias, exh. book. (Yerevan, 2006), p. 3.

7 Michel Foucault, “Power and Body”, Intellectuals and Power, Vol. 1 (Moscow: Praksis, 2002), pp. 166, 169 (Russian translation).